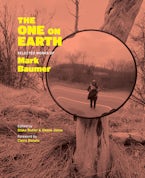

Mark Baumer was a prolific writer, activist, and digital native. Born and raised in Durham, Maine, he was a graduate of the MFA program at Brown University, after which he became a "web content specialist," a climate activist, and a labor organizer in Providence, RI. A member of the group FANG (Fighting Against Natural Gas Convergence), he walked barefoot across America to draw attention to climate change. His work is continued by the Mark Baumer Sustainability Fund.

Blake Butler is the author of five book-length works of fiction, including 300,000,000 (Harper Perennial), Sky Saw (Tyrant Books), There is No Year (Harper Perennial), Scorch Atlas (Featherproof Books), and Ever (Calamari Press), as well as the nonfictional Nothing: A Portrait of Insomnia (Harper Perennial). His fourth novel, Alice Knott, will be published by Riverhead in 2020. His short fiction, interviews, reviews, and essays have appeared widely, including in The Believer, The New York Times, Bomb, Bookforum, and as an ongoing column at Vice. He is a founding editor of HTMLGIANT and currently serves as editor of the Fanzine. He lives in Atlanta.

Shane Jones is the author of the novels Light Boxes—which has been translated in eight languages and was named an NPR best book of the year (2010)—Crystal Eaters, Daniel Fights a Hurricane, The Failure Six, and Vincent and Alice and Alice, as well as the short story collection I Will Unfold You With My Hairy Hands and the poetry collections A Cake Appeared and Paper Champion. He lives in Albany, New York.